Members of the Los Angeles Printmaking Society Facebook group may know me because I post about my podcast, Platemark, when new episodes drop bi-weekly. For the rest of you, I’d like to introduce myself. First, know I’m not an artist; rather, I am an admirer of art (contemporary prints are a favorite). As a former museum curator, there are many aspects of your world in which I’d love to live, but my talent is minimal, so as an admirer I must remain. Now I’m independent and am loving creating Platemark. I also started a fine art print fair in Baltimore (I directed the Baltimore Museum of Art’s last three print fairs in 2012, 2015, and 2017.) Our second fair is coming up at the end of March: March 30–April 2, 2023. All the details are over at baltimoreprintfair.com.

So what can I offer members? I’ve been a curator my entire career and I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about what makes a work of art “great.” When LAPS editor Cathie Crawford asked me to write for the new blog, I thought it would be a good opportunity to share my thoughts.

When you’re not involved in the making of objects, it’s easy to disassociate the object from the maker. But I try to always keep the artist in mind: not only their aims with the work, but also their background, training, life experiences. You all are well aware that the concept of a work starts deep inside the artist’s creative self. I think of it this way: at the very base of creating a work of art is the circle of mind/heart/hand. The concept born in the artist’s brain must pass through their heart because it’s the artist’s passion that makes its creation necessary. All of that must come out through the hand as the artist’s technical facility brings the passion-infused idea into being. All three elements are essential.

A huge part of the curator’s job is to assess a work of art. That assessment is individual and can take many forms. My friend and Platemark co-host, Ben Levy, tries to put himself in the artist’s mind and reverse engineer the making of the print. He imagines every decision point—what is the size of the edition, how big is the matrix, what is the technique, what is the subject—to see if the work aligns with what he imagines the artist’s intention might be. I think this comes easily to him because he is a trained printmaker.

When I’m assessing a work of art, several things happen. First, I run through my mental slide carousel of works I’ve seen over the course of a long career in museum print departments and wandering print fairs and galleries. I’m looking for other works that are cousins of the work in question. That helps me fit it into a genre or way of thinking.

Second, I think through a litany of questions that fall into two big categories: visual impact and emotional impact. I’ve written about the list of questions I ask of the work in other places, but the more I think about it, I think I can reduce it down to one core idea. The visual impact and the emotional impact go hand-in-hand. A striking image will elicit an emotional response and a powerful message in a print will make the visual parts more compelling.

One aspect I talk with artists about a lot is the idea of reducing elements to the essentials. Wasn’t it Coco Chanel who counseled women to take off one accessory before leaving the house? I feel similarly about images. If there are multiple elements that point to one idea, could the work say the same thing without all of them? This leads to a clarity of thought and presentation. There is a certain beauty in simplicity. In addition, your audience will likely have an easier time understanding your intentions.

When I find a work that hits the mark, it’s like the last piece of a puzzle has been placed. It’s a weird sensation, but you just know it’s the right thing. Of course, when acquiring for a museum, there are multiple people who need to agree with your assessment. Being able to articulate why the work fits in the collection is critical. In the art biz, getting over one’s fear of public speaking is incredibly important. But there is an aspect of the whole enterprise about which curators must be cautious: their own taste and sense of style. One is always questioning whether one’s own taste is affecting choices. I think it’s inevitable.

Since I left my museum position behind five years ago and am now independent, things are a bit different. I miss the objects in the collection, particularly those that I shepherded in. The bar for acquiring prints was pretty high at the museum. Prints had to have what we came to call conceptual rigor. That meant they were more than decorative—pretty didn’t cut it in the museum. But my attitudes have changed since being released from the confining parameters of an institutional collection. The truth is beauty is a deeply inherent need for humans. We crave it and get immense satisfaction from experiencing it. Have you ever gotten goosebumps listening to a symphony, experiencing architecture, or coming upon a wide-open vista? I’m no scientist, but I feel like endorphins must be released. Living with pure beauty is a nearly urgent need.

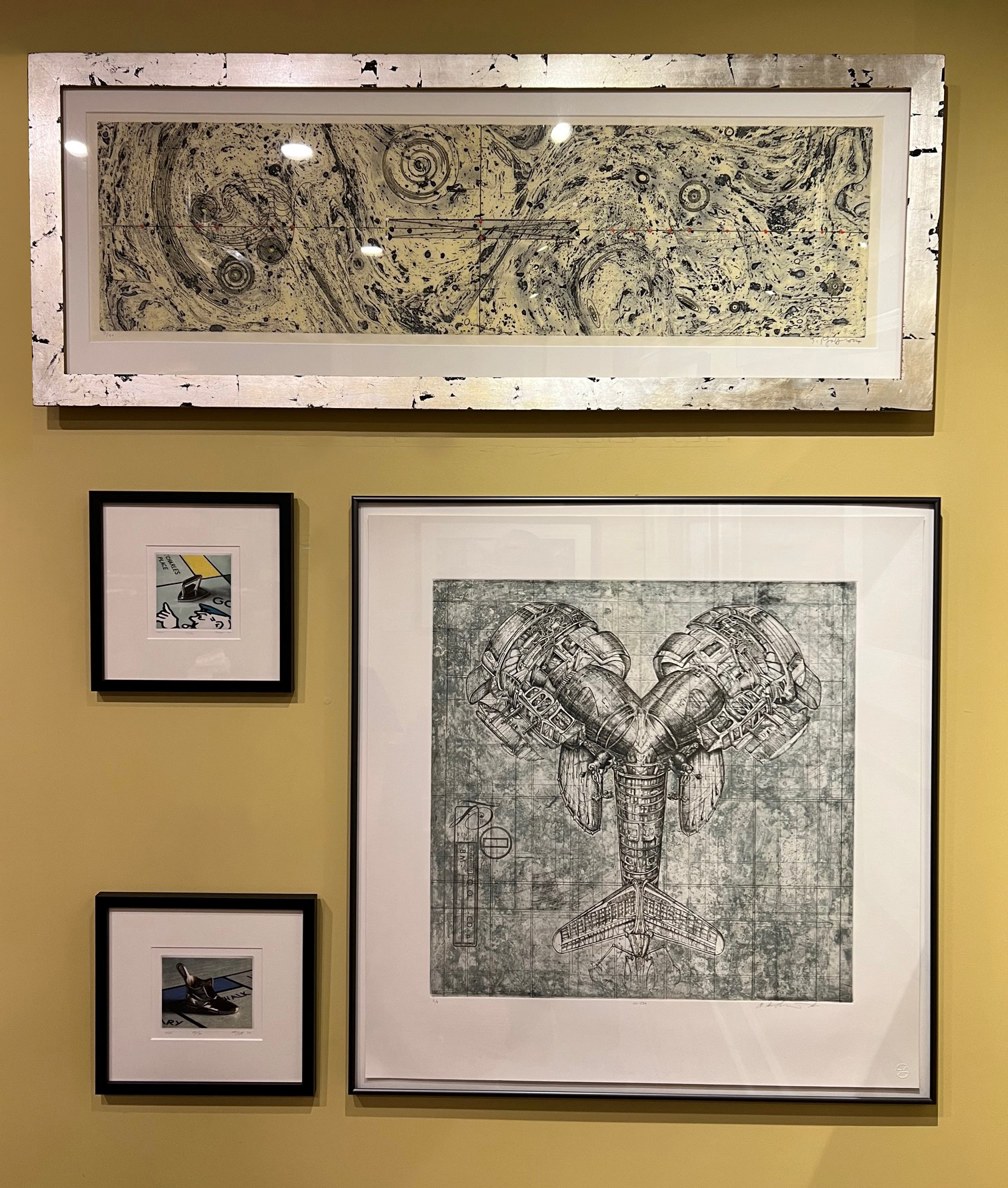

Prints are wonderful. Their lower price point means they are widely accessible. Their multiplicity means I can have one and so can you. Their production often requires a team of printers, publishers, and gallerists who back the artist and their work. The result is an entire ecosystem of people working towards keeping prints relevant and in the forefront. And the ecosystem is full of the nicest and most hardworking people (keep up the good work!). I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else.